Trump the peacemaker? Not yet.

Plus, Damon Linker on the far-right ideas driving Trump’s exercise of presidential authority

The Trump administration is seeking to renew a nuclear pact with Iran while the president personally warns Israel’s prime minister not to strike Tehran.

President Trump seems fed up with Russian President Vladimir Putin, exclaiming on social media that the autocrat in the Kremlin must have gone “absolutely crazy” after Russia showered Ukrainian cities with hundreds of murderous drone and missile strikes.

The White House is still trying to broker a ceasefire in Gaza, too, by sending “an Israeli-backed ceasefire proposal to Hamas,” according to The Washington Post in a report this morning.

Maybe a breakthrough in one or more of these conflicts is in the offing. As I write this newsletter, Donald Trump is running into a slew of problems – some of his own making, some outside his control – preventing him from fulfilling his promise to bring peace to violent corners of the world and defuse tensions with rivals.

All this was to be expected, of course, despite the president’s mindless bluster that he would end the Russia-Ukraine war in 24 hours or that Gaza would be better off rebuilt as a “Riviera of the Middle East” without Palestinians. Mediating peace has always been difficult, and more intelligent, less cynical presidents than Donald Trump have met failure.

Trump’s blunders

In today’s episode of History As It Happens, historians Jeremi Suri and Jeffrey Engel talk about what it takes to be a successful peacemaker.

Personal charisma and friendship will only take a president so far. Yet throughout last year’s campaign and the first four months of his term, Trump repeatedly claimed that his familiarity with both Putin and Ukraine’s Volodmyr Zelensky would help produce immediate success.

Not only has the U.S. president failed to entice Putin to play nice, but he’s also made a series of unforced errors that have upset Ukraine and the European allies. For instance, rather than imposing sanctions after the Kremlin rejected a 30-day ceasefire proposal, Trump let Putin talk him into giving him a pass during a two-hour phone call, as Michael Weiss reports for New Lines Magazine.

To escape additional sanctions, Putin pried another delaying tactic from the dealmaker-in-chief: to continue direct talks between Russian and Ukrainian negotiators in Istanbul. Weiss says, “The Istanbul conference predictably went nowhere because Russia sent its B-team delegation to Turkey.”

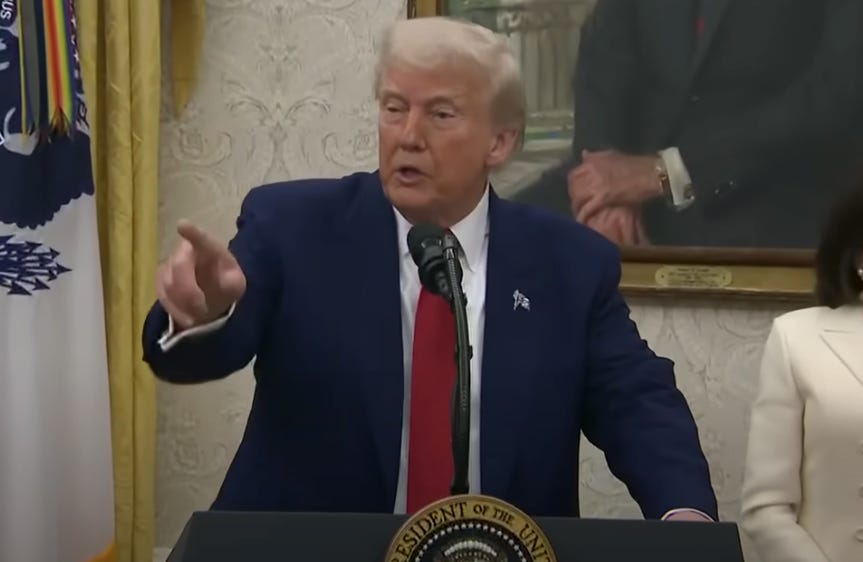

On Wednesday, Trump finally conceded that Putin might be playing him. At a White House news conference, the president was asked, “Do you still believe that Putin actually wants to end the war?”

“I can’t tell you that, but I will let you know in about two weeks, within two weeks. We're going to find out very soon. We're going to find out whether or not he's tapping us along or not. And if he is, we'll respond a little bit differently,” Trump answered.

On top of tactical blunders, the president seems temperamentally unsuited to acting as an impartial broker. Can you imagine him berating Putin in the same way he lashed into Zelensky at the White House on Feb. 28? It would never happen. Moreover, as we’ve discussed in past newsletters, Trump pressured Ukraine to begin negotiations from the position that it started the war and Russia was the aggrieved party, a perverse distortion of reality.

Trump “fundamentally believes that Vladimir Putin and other powerful figures around the world will take him seriously for blustering and threatening and talking big without following up,” Jeremi Suri says in the podcast.

“The world of international politics is a world of action, at least as much as it is of rhetoric. It’s different from real estate development and other fields that may be more driven by talk. Already, most of America’s counterparts have realized that Trump makes huge demands and then slowly but surely backs down.”

Suri continues: “The second mistake [Trump] is making is believing that he and Vladimir Putin share certain interests. He falls into the classic case of a strongman who sees himself in other strongmen but doesn’t recognize that… they have very different interests… Trump overrates how he can persuade Putin and underrates the importance of the Ukrainians.” (In last week’s newsletter, I shared historian Antony Beevor’s take on the Trump-Putin dynamic: Trump doesn’t realize Putin loathes him.)

Leaning too heavily on personal charisma in high-stakes negotiations is a “classic mistake,” says Jeffrey Engel, the founding director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University.

“We know policymakers throughout the world do not care as much about friendship as they do their own state’s interests. This is one of the interesting things about Trump’s ‘America First.’ I contend that every policymaker – Democrat, Republican, libertarian, it doesn’t matter, for the last 250 years in our country – is trying to do what’s best for the country and put America first,” Engel says.

The historian continues: “Having said that, one of the things Trump needs to think about, looking at past examples from successful presidential peacemakers, is this is a very time-consuming process. You don’t build relationships overnight. Obviously, Trump and Putin have some kind of relationship that goes back years, and some people might speculate how deep that relationship is, but as a president, you can’t call up someone on the first day and say, Hey, I think we should be friends. Now do what I want.”

In other words, Trump undermined his negotiating position with his repeated boasts that his personal connections would help end the war quickly and easily. He needs to put in the work.

Suri and Engel contrast Trump’s style with that of Jimmy Carter, who secluded himself for thirteen days at Camp David in 1978 with Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, ultimately producing lasting peace between Israel and Egypt (but notably failing to resolve the Palestinian issue). The historians note that the difficulties notwithstanding, both Israel and Egypt’s leaders were at least ready to lay down their arms after decades of war. Putin, on the other hand, still seeks to dominate Ukraine.

Personal perils

One example we did not discuss took place in Europe in 1938. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s excessive self-confidence at Munich epitomized the perils of personal diplomacy in matters of war and peace.

In the second of her monumental two-volume study of interwar Europe, the late historian Zara Steiner wrote that although Chamberlain believed he had succeeded at Munich – “Hitler blinked” – it proved to be “a short-run victory.”

“The whole point of Chamberlain’s meetings with Hitler was to establish a personal relationship with the Führer and to make accurate assessments of his motives and objectives. Yet Chamberlain’s reading of Hitler’s intentions was fatally flawed. Like Roosevelt and Churchill in their later dealings with Stalin, the prime minister thought he had created a bond with Hitler and had won his respect. Chamberlain told his colleagues that he ‘had now established an influence over Herr Hitler, and that the latter trusted him and was willing to work with him…’”

“... Just as important as the prime minister’s excessive self-confidence was his misplaced assumption that Herr Hitler must share his own abhorrence of war. By nature, Hitler was willing to take risks which Chamberlain would not contemplate. There was a more basic difference between the two leaders, and it was one which Chamberlain never fully grasped. Hitler was preparing for war, not just war with Czechoslovakia but war with the western powers.” – Zara Steiner, The Triumph of the Dark, p. 651

As a distant observer of the Trump-Putin dance, I can only speculate that a similar dynamic is playing out today. Donald Trump has horrendous judgment in people and overblown self-confidence in his dealmaking skills; he is the opposite of the reality-TV businessman he portrayed on The Apprentice. If I can see that he’s a blustering showman, so must Vladimir Putin. However, the showman is the most powerful officeholder in the world, and one can never be sure when Trump might exercise the leverage he has at his disposal.

Also covered in the podcast with Jeffrey Engel and Jeremi Suri: Teddy Roosevelt and the Russo-Japanese War; Nixon and Kissinger as “men of peace;” Reagan and Gorbachev; Bush and Gorbachev; Clinton and Northern Ireland; Clinton and Oslo; Obama’s undeserved Nobel Peace Prize; and much else.

We did not get around to Joseph Biden, but I offered an early judgment in my opening monologue. Biden enabled Israel to destroy Gaza and kill thousands of Palestinian men, women, and children. He made no discernible progress in ending the Russia-Ukraine war or toward renewing the Iran nuclear deal. It’s not clear he tried very hard, as he had lost his marbles at some point. Thus, as a peacemaker, Biden was an utter failure.

Jeremi Suri teaches history at the University of Texas at Austin and co-hosts This Is Democracy podcast. He also writes Democracy of Hope newsletter with his son Zachary.

SMU’s Engel is the author of When the World Seemed New: George H. W. Bush and the End of the Cold War.

The ideas behind Trump 2.0

Political theorist Damon Linker has written the best short essay to date (at least that I have read) explaining the ideas driving Donald Trump’s approach to exercising executive power. His is not an explanation of the rise of right-wing populism in America that examines, say, the role of NAFTA in accelerating deindustrialization. Linker is rather interested in decades-old, far-right ideas that now influence Trump’s use of power.

In The New York Times, Linker traces the origins of theories positing that a president has unrestrained authority, that he can do whatever he wants to rescue the republic from a dire emergency. Or, in the case of the Trump administration, an imaginary permanent emergency that justifies its hurricane of executive orders and bullying lawsuits.

“Those arguments — imported from Europe and translated to the American context — have risen to greater prominence now than at any time since the 1930s,” he writes.

Unlike historians and political scientists who’ve spilled oceans of ink trying to prove Donald Trump is a fascist, Linker correctly zeroes in on a tradition that “begins with legal theorist Carl Schmitt and can be followed in the work of the political philosopher Leo Strauss, thinkers affiliated with the Claremont Institute, a California-based think tank with close ties to the Trump movement, and the contemporary writings of the legal scholar Adrian Vermeule.”

To these thinkers and their disciples in the Trump administration, the administrative state is an obstacle to presidential supremacy. In their view, all the federal bureaucrats, lawyers, and experts (who held no influence before Progressive Era reforms) lack any constitutional authority to thwart a president’s agenda.

I suppose you can dismiss this as fascism and move on. Linker instead seriously engages with these ideas, even if Trump has never read Schmitt or Strauss. His lieutenants — or the thinkers who influence his lieutenants — have.

In Tuesday’s episode of History As It Happens, Linker explained how he identified the connection between the far-right theorists and Russell Vought, the government-slashing OMB chief; when these ideas began entering the Republican Party’s mainstream; Reagan, Cheney, and ‘unitary executive’ theory; Schmitt’s historical importance; the Biden debacle and Democrats’ denialism; and much else.

Damon Linker writes the Notes From the Middleground newsletter.

What’s next?

In Tuesday’s episode, historian Jim Oakes will return to talk about Lincoln, habeas corpus, and presidential war powers.

In Friday’s episode, historian Kevin Ruane will appear in my annual D-Day episode. This year, the subject will be D-Day in film – and the cultural work such movies do.

I became interested in WWII as a teenager in no small part because of The Longest Day, the 1962 Hollywood epic. To my young eyes, it seemed so realistic. Then, one Christmas, my half-siblings’ father gave me John Keegan’s The Second World War. The rest, as they say, is history.

In next week’s newsletter, I’ll share my library of D-Day-related podcast episodes. Your “homework” until then is to watch The Longest Day.