David M. Kennedy on due process in war and peace

Plus, Laurence Rees takes us inside “The Nazi Mind”

On February 19, 1942, FDR signed an order that would go down in infamy:

“Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage… I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War… to prescribe military areas… from which any or all persons may be excluded… The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents… such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary…”

There is no mention of internment camps or any ethnic group in Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt ten weeks after Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, plunging the country into the Second World War.

“No explicit reference to the Japanese was necessary,” historian David M. Kennedy wrote in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Freedom From Fear. “The original order neither prescribed what should happen to the evacuees nor precluded voluntary withdrawal.”

“When [Attorney General Francis] Biddle feebly objected that the order was ‘ill-advised, unnecessary, and unnecessarily cruel,’ Roosevelt silenced him with the rejoinder, ‘This must be a military decision.’” (Kennedy, p. 753)

Out of “military necessity,” in a climate of racist paranoia and rumor, what transpired from late February to August 1942 amounted to one of the ugliest civil rights violations in U.S. history. More than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — roughly two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens — were forcibly moved to assembly centers such as racetracks or fairgrounds, where they would await transport to a permanent camp.

Before the heavy hand of government swept these harmless people from their homes in California, Oregon, and Washington, some 15,000 Japanese “took it upon themselves to leave the prohibited Pacific coastal zone” (p. 753) during a brief period of voluntary withdrawal. And voluntary compliance with Exec. Order 9066 might have become the norm had it not been for deeply ingrained, decades-old prejudices against Asian immigrants that were now boiling over during wartime.

“Many states in the nation’s interior made it clear that Japanese migration eastward spelled trouble. ‘There would be Japs hanging from every pine tree,’ the governor of Wyoming predicted, if his state became their destination. ‘We want to keep this a white man’s country,’ said the attorney general of Idaho, urging that ‘all Japanese should be put in concentration camps.’” (p. 753)

From citizens to internal enemies

Donald Trump is the first president to invoke the Alien Enemies Act since FDR, and the first to do so during peacetime. A federal judge struck down Trump’s novel use of the 1798 statute because there was no legal basis for summarily deporting suspected Venezuelan gang members. Neither a gang nor the Venezuelan government is at war with the U.S. There is no invasion.

When it came to German, Italian, and Japanese aliens (non-citizens), Roosevelt was on sturdier legal footing when he invoked the Alien Enemies Act shortly after Pearl Harbor. The legislation reads:

“Whenever there shall be a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government… all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government… who shall be within the United States, and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed, as alien enemies.”

“Government surveillance, ongoing since 1935, had identified some two thousand potentially subversive persons in the Japanese community,” Kennedy wrote (p. 749). Several thousand Japanese, German, and Italian alleged “security risks” were rounded up in the final days of 1941.

In mid-January, Roosevelt issued Proclamation No. 2537, requiring these aliens to register with the Department of Justice to receive a Certificate of Identification for Aliens of Enemy Nationality. “Government officials eventually arrested nearly 9,000 Japanese immigrants, in addition to 11,500 German and 3,000 Italian detainees,” according to densho.org.

Had the crackdown gone no further than these arrests by federal law enforcement agents of suspected spies and saboteurs, few Americans today might look back with burning disapproval at the government’s behavior during those nervous months after Pearl Harbor. But it did not stop there. Executive Order 9066 empowered the War Department to act out of “military necessity” to evacuate U.S. citizens.

Stretching and shredding the Constitution

As I said to David Kennedy in Friday’s episode of History As It Happens, even in a supposedly liberal democracy, once a racial minority or marginalized group comes under suspicion and is turned into a category of undesirable people – in large part because influential media and political figures constantly demonize them – the government can conjure some warped legal reasoning to shred the Constitution.

During the Second World War, major military and legal figures fabricated preposterous allegations of espionage and sabotage to justify holding Japanese in concentration camps. Today, President Donald Trump defines undocumented immigrants as synonymous with crime and cultural death. Thus, they have no rights he’s obligated to respect. No court (or facts) may stand in the way of his deportation scheme.

“I don’t think this is a behavior or a property exclusive to our society. It’s just part of human nature,” Kennedy says in the podcast.

“And let’s remember, there’s a very important distinction in terms of context between that moment and [the current one]. It was wartime, and the United States had officially declared war, which it had only done five times in its entire history. Once war is officially declared by the Congress, all kinds of legal, structural, and institutional arrangements fall into place behind that. There is nothing comparable going on today. And what’s unprecedented about the scope, scale, and velocity of the current situation is it’s not wartime or any comparable crisis.”

Non-citizens living in the United States illegally are subject to deportation, although many — including Kilmar Abrego Garcia — enjoy protected status to keep them from being returned to certain persecution or death. They are all entitled to basic rights under the Constitution. There’s also the matter of whether it is wise, whatever the legality, to deport a large part of the American labor force, an economically indispensable population in the agriculture, service, construction, and hospitality sectors.

Yet the president, unmoored from reality, has told multiple interviewers that he doesn’t know if he is obligated to uphold the Constitution or respect due process.

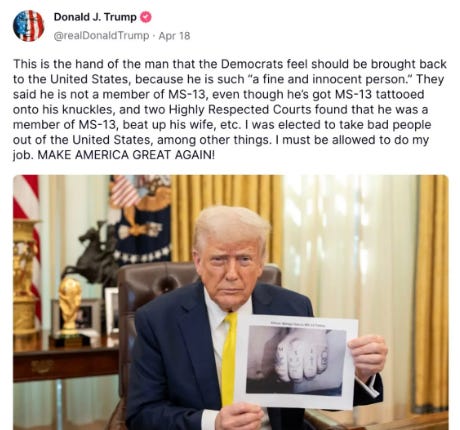

In a mind-boggling exchange with ABC’s Terry Moran (begin watching at 22:00), Trump insisted that the knuckles of the wrongfully deported Abrego Garcia were tattooed with M-S-1-3, to signify his membership in the notorious gang. When Moran informed the president that the photo in question had been altered – and that Garcia’s actual tattoos may have no gang affiliation at all – Trump would not let go of the lie.

“That was photoshopped?” Trump asked incredulously. “Terry, you can’t do that… He has MS-13 tattooed. Terry, Terry, do you want me to show you the picture?”

“I want to move on to something else,” Moran haplessly responded. “I saw the picture. We’ll have to agree to disagree.”

“Don’t photoshop it. Go look at his hand,” Trump shot back. “He has M-S as clear as you can be… This is why people no longer believe the news, because it’s fake news.”

If friends or family members were to act this way, you would think they had lost their bearings. Your deranged uncle, however, does not have the authority to try to deport 10 million people. The administration is seeking $45 billion to build new detention centers and pay for related security and transportation services – an envisioned complex of cages 80 years after Japanese-Americans were locked up behind barbed wire despite not a single credible allegation of wrongdoing.

“Even in World War Two, in the situation of the Japanese population on the West Coast and in Hawaii, where most Japanese were concentrated at the time, right from the outset, there were misgivings about the evacuation order and later the internment, which are two separate matters,” says Kennedy.

He adds, “The incarceration in the camps was never formally adjudicated. People often mistake the famous Korematsu case for a judgment about the camps. It’s not. The Korematsu case was about the evacuation order.”

The American Civil Liberties Union represented Fred Korematsu in his lawsuit challenging his arrest on May 30, 1942. Today, the ACLU is suing the Trump administration to stop its illegal use of a wartime statute to stuff human beings into foreign prisons, another parallel between past and present.

Also discussed with David M. Kennedy in the podcast: history of anti-Asian discrimination in America from the late nineteenth century; panic after Pearl Harbor; General John DeWitt and Attorney General Francis Biddle; why Roosevelt paid almost no role in writing Exec. Order 9066; infamous footnote in Korematsu; Japanese who evaded the camps and lived out the war unmolested.

(Note: Kilmar Abrego Garcia was not wrongfully deported under the Alien Enemies Act, but rather regular immigration laws, despite an order that he not be sent to El Salvador. Gabe Fleischer explains here.)

Remember, History As It Happens is available on all major podcast platforms. New episodes are published every Tuesday and Friday at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you find your favorite shows.

Inside the Nazi mind

If, as David Kennedy said, it’s simply part of human nature to suspect Them of threatening or endangering Us, then history can provide valuable warnings that transcend a particular society or moment in time.

The Nazis were in many respects unique. But their mentalities were human. In Tuesday’s episode of History As It Happens, the acclaimed documentarian and author Laurence Rees talked about his new book, The Nazi Mind: Twelve Warnings From History, where he applied the discipline of psychology to approach why, for instance, some people found Hitler captivating.

Or why German doctors voluntarily murdered the mentally disabled. Or how people coped with killing their victims up close or at a distance: the gas chambers were not constructed to speed up the pace of genocide, or make it more “efficient.” Rather, the architects of the Holocaust were trying to make mass murder easier on the psyches of the killers by physically separating them from their victims at the time of death.

Conspiracy theories circulated in the Nazi movement’s lifeblood from the start – and on the German nationalist, or völkisch, right more broadly. In searching for scapegoats upon whom to pin defeat in the First World War, Hitler and like-minded men zeroed in on Jews, socialists, and other foreign elements – the “stab in the back” myth.

“The latest psychological research demonstrates that this attempt at scapegoating fits into a typical pattern,” writes Rees. “The social psychologist Professor Karen Douglas believes that as most conspiracy theorists are ‘looking for someone to blame,’ the idea that ‘there are these people pulling the strings behind the scenes’ helps deal with their ‘feelings of powerlessness and disillusionment.” (The Nazi Mind, p. 19)

This is a work of history, not psychology. And Rees’ scholarship is informed by a career interviewing people who were citizens, perpetrators, or victims of the Third Reich. The Nazi Mind is not a work of political commentary. Rees leaves it to the reader to apply his warnings from the past as they choose. As an American, I thought of the crisis of democracy in my country as I made my way through this excellent book. For instance, why is it that some people see Donald Trump as a messiah when, to my mind, he’s a deranged, dangerous buffoon. Can we learn anything helpful by studying Hitler’s “charismatic hold” on the German masses?

“Each situation is unique,” Rees says in the podcast. “But you can certainly point to something fundamental that’s going on with Hitler that’s interesting in broader terms. There’s a massive overemphasis in popular culture about the great charismatic leadership of Hitler, that he looks in your eyes and you immediately succumb, and so on.”

“Hitler hypnotized nobody. He may have fit the classic definition of Max Weber, the German sociologist, who defined charismatic leadership… but that doesn’t mean that he’s convincing people by some kind of supernatural talent. I’ve met people who heard Hitler talk in the early 1920s who thought he was incredible and wonderful. I’ve met other people who heard him talk who thought he was a complete jerk. So it depends on what you’re bringing to it.”

In other words, Germans who were already inclined to agree with Hitler’s ideas could find him captivating. But intoxicating oratory was not enough. Rees reminds me that in 1928, the Nazis received 2 percent of the vote in the federal election. Where was Hitler’s charisma then? It took the Great Depression and the worsening of the Weimar Republic’s political crisis for Hitler and the Nazis to persuade a wider audience. Timing is everything in politics.

Also discussed with Laurence Rees: Us vs. Them at the heart of Nazism; what makes propaganda and hyperbole effective; German doctors and mass murder; public protest in the Third Reich; why the elites underestimated Hitler; Nazism’s appeal to the youth; and much more.

What’s next?

In next Tuesday’s episode, Omar Rahman of the Middle East Council on Global Affairs will answer: what happened to the Palestinian Authority? During the Palestinians’ darkest hour since the 1948 Nakba, their leadership is ineffectual and irrelevant.

In next Friday’s episode, Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft will explain why India and Pakistan are still fighting a “forever war.”

Let’s talk!

I’m thinking about hosting a monthly video chat for my ~2,000 Substack subscribers. You would need the Substack app on your phone or desktop to participate. We would talk about recent episodes and engage in thoughtful conversations about the historical origins of current events.

Let me know if you’re interested. My email is martinjdicaro@gmail.com