I’m stuffed not only with roast turkey and sweet potatoes. I can’t swallow another election postmortem.

The past twenty-four days have witnessed a hurricane of articles and essays, written by esteemed journalists and amateur Substackers, assessing questions big and small. Some argue Kamala Harris lost because of economic concerns, namely high inflation. To others, “woke” social justice causes alienated socially conservative working-class people. Some blamed the Biden administration’s support of Israel. Or Biden’s decision to run for a second term until it was “too late.” Or the toxic influence of right-wing media. Or a combination of these reasons among many others.

Some of these takes are convincing. After all, recent presidential elections have been decided on the margins. Thus, the argument goes, if Harris had simply stressed this position instead of that one, or had appeared on this podcast instead of that one, she may have tilted the electorate in her favor.

Such small-bore analysis can only take us so far because it elides larger structural forces at work in the world today – a world where the establishment and incumbents are on the defensive. If we broaden our perspective – if we glance back at the decades-long exodus of working-class Americans from the Democratic Party – we realize that quibbling over how Harris might have eked out a 2-point victory over Donald Trump misses a more important point.

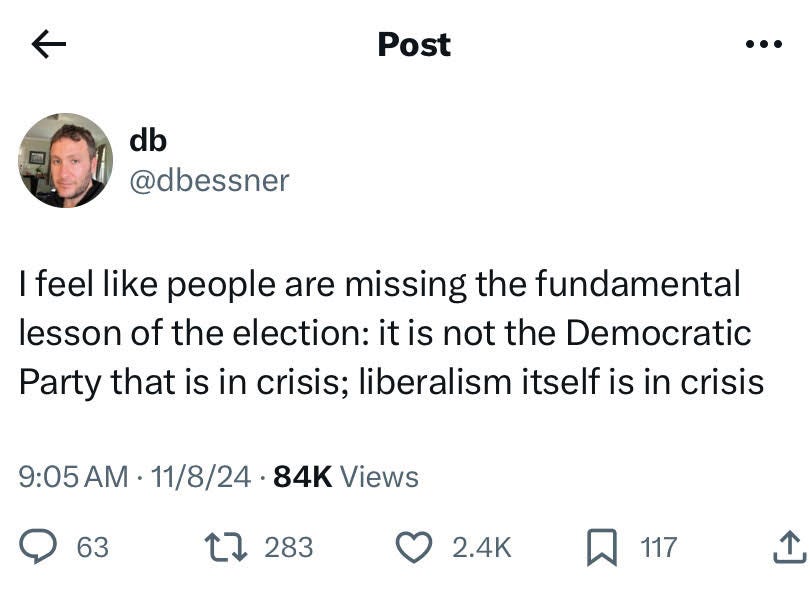

Here is University of Washington historian Daniel Bessner on Nov. 8, three days after the vote.

To understand why voters were willing to reward Trump, a corrupt, illiberal figure of absolutely no character or competence, with a return to the White House, we cannot begin our analysis with, say, the events of July 21, 2024, the day President Biden belatedly withdrew from a race he would have lost in humiliating fashion. Figuring out where to begin this story isn’t easy. The history of liberalism, the dominant political and governing philosophy of the American Century, is a sprawling subject. Its definition is contested. Yet a podcast host must choose for the sake of conversation.

Let’s start in 1945

In Friday’s episode of History As It Happens, Bessner, who co-hosts with Derek Davison the popular American Prestige podcast, deconstructed my chosen (and familiar) narrative. It begins in 1945.

Here is how the story goes:

The legislative and institutional achievements of the New Deal and the U.S. victory in the Second World War led to the most prosperous quarter-century in the country’s history. Labor union membership soared along with home ownership. Income inequality was not nearly as severe as it is today. Liberal internationalism reached new heights with the establishment of the United Nations, NATO, World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

The early post-war period also witnessed the creation of the U.S. national security state and enormous arsenals of nuclear weapons. Americans could have guns and butter. Liberalism was anti-communism; both major political parties were committed to containing Soviet Communism while differing over the extent of “communist subversion” at home. A degree of racial justice was delayed, only arriving in the mid-1960s with the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, a century after the abolishment of slavery.

Then came Vietnam, urban riots, assassinations, Watergate, inflation, stagflation, oil shocks, deindustrialization, and recession. After these traumas and humiliations, however, liberalism (or neoliberalism) emerged untrammeled from the end of the Cold War. Suddenly, the USSR was gone, market economies and democratic elections proliferated, NAFTA passed with bipartisan support, and for a time it looked like even Russia or China might be on the road to political liberalization.

A generation or two after the heady 1990s, one struggles to see even wisps of such optimism. The techno-triumphalism that pervaded the late Clinton years proved to be an illusion, as Nelson Lichtenstein has argued in his excellent book. Computers, the internet, and Silicon Valley didn’t magically solve our Rust Belt problems. In 2016, a candidate who railed against the free trade consensus and mass migration (caused in part by NAFTA) won the presidency.

Maybe you find this chronology wanting, but it made for a lively conversation with Daniel Bessner, whose scholarship focuses on U.S. foreign policy and international relations.

After 1945 “New Dealers-cum-Cold War liberals seized the reins of the American state and institutionalized their philosophy. They like private property. They like elites. They like tinkering with the government. They like forms of social democratic welfare, particularly those connected to military spending,” Bessner said.

“This became the dominant ideology of the United States since 1945 against which other people defined themselves. Even Ronald Reagan who reshaped the New Deal order is operating within a liberal framework, broadly speaking. In some sense, Reagan is just a particular type of liberal who emphasizes private property and freedom from government interference as opposed to more social democratic liberals who favor social welfare programs.”

“What is happening now,” Bessner continued, “is that liberals have been ossified. They are sclerotic. They are unable to make changes to their positions so that they’re able to actually address the fundamental economic problems that face Americans. This is reflected in the Democratic Party which has been totally professionalized. The professional-managerial class essentially runs [the party], goes to a relatively small number, let’s say, top-50 or top-100 colleges, and has particular beliefs about the world, the economy, foreign policy, and culture that aren’t necessarily speaking to the interests of most Americans.”

A good example of this disconnect can be found in foreign policy. The Biden administration since its very first day has loudly defended the maintenance of the “rules-based international order” – the institutional and legal framework governing interstate relations since 1945. It has supported Ukraine against Russia and Israel as it destroys Gaza while maintaining the Trump tariffs against Chinese imports.

How exactly, working-class Americans must wonder, did any of this help them? What kind of “rules-based order” necessitates supporting a country, Israel, whose leaders are charged with crimes against humanity? While Ukraine’s cause is just, one doesn’t need an advanced degree in military studies to understand that it cannot fight Russia indefinitely, that at some point a negotiated settlement must be reached. Where has our somnambulant president been?

Among the subjects Bessner tackles on the podcast are liberalism’s nineteenth-century European origins; its relationship with capitalism and its tendency to lead to periodic destabilizing crises; Fukuyama and the end of history; the misplaced optimism of “the new economy” of the late 1990s; the failings of the “war on poverty;” and whether the world is entering a new illiberal era of populist autocrats and autocratic capitalism.

The evolution of Thanksgiving

In Tuesday’s episode of History As It Happens, historian David Silverman poked necessary holes in the childish myths of “the first Thanksgiving” during a wide-ranging conversation about the holiday’s evolution over the centuries to a secular, commercialized, yet still family-centered day on the calendar. Feast! Football! Christmas shopping!

“The main way that it’s evolving today is that a growing portion of society is becoming aware that the mythical story of Pilgrims and Indians can’t hold up to the truth of history, and that the myth does real damage to native people in terms of their lived experience,” said Silverman, an expert on colonial America and Native American history at George Washington University.

Silverman works with primary and secondary school teachers on how to teach the relationship in early seventeenth-century America between English settlers and native peoples. Whereas I – born in 1975 – was taught myths about the Pilgrims’ friendly relations with the Indians forever memorialized in a dramatic painting of the “first Thanksgiving,” today schools are dropping Thanksgiving pageants where students would dress up as English religious separatists and docile natives (the Wampanoags), Silverman said.

Colonialism, said Silverman, was a nasty, bloody business. So rather than give children a false impression that they may carry into adulthood, it’s wiser to teach this important history when students are old enough to understand it. Moreover, it’s possible to celebrate this quintessential American holiday without any reference to the Pilgrims. For generations spanning more than two centuries, European immigrants-cum-Americans observed episodic days of thanksgiving and official Thanksgiving holidays that weren’t even vaguely connected to the history of Plymouth Colony.

It was not until the 1840s, when the Reverend Alexander Young discovered the Pilgrim Edward Winslow’s contemporaneous account from 1621, that the “first Thanksgiving” began entering the public’s imagination. This coincided with the mass immigration of Catholics from Ireland and Germany, compelling the white Protestant majority to lend a foundational importance to the Pilgrims to defend their cultural prominence.

And then there was Sara Josepha Hale, the first female magazine editor in America. Her Godey’s Lady’s Book popularized Thanksgiving customs and recipes, and she personally lobbied the federal government to establish a national Thanksgiving holiday. Abraham Lincoln finally did so in 1863.

National origin stories are amalgams of truth and myth. If the purpose of an origin story is to foster national unity centering around a shared ethnic, religious, linguistic, geographic, and/or religious background, then myths seem indispensable.

America was founded on ideas – not a shared ethnicity, religion, or language. Thus, the story of Pilgrims and Indians works to forge a common link to the past among diverse people. The “first Thanksgiving” evokes America’s immigrant origins – we have always been a nation of immigrants – as well as a sense of bravery, resilience, patriotism, tolerance, even racial harmony. All good and admirable things! The problem is, the story isn’t true. And as Silverman says in our conversation, our patriotism should be built upon the truth.

Oh, the feast that happened in the autumn of 1621 was an accident anyway. As Winslow noted in his account, the English settlers fired their guns in celebration, attracting the attention of some ninety Wampanoag warriors who arrived at the colony thinking it was under attack. There was no attack, so they sat down and feasted.

What’s next?

Coming up in Tuesday’s episode, historian Omer Bartov will return to the podcast to discuss the question of genocide as it pertains to Israel’s war in Gaza. Bartov penned one of the most searching, sobering essays about Israeli history and society that I’ve read in 2024. It can be read without a paywall at The Guardian.

Next Friday, historian Michael Kimmage will discuss his article, co-written with Hanna Notte, in Foreign Affairs about the war in Ukraine. Dec. 5 will mark the thirtieth anniversary of the Budapest Memorandum – a set of assurances that prohibited Russia from violating Ukraine’s sovereignty in exchange for Kyiv ceding the nuclear weapons left on its territory with the USSR’s collapse. As it turned out, the assurances were hardly worth the paper they were printed on.

Something less depressing

My Thanksgiving feast. I cooked all afternoon for a table of three. Yes, I have plenty of leftovers.

I made roast turkey with bourbon apricot sauce, sweet potatoes, Brussels sprouts, green bean casserole, and stuffing with Italian sausage. I can appreciate the talents of food photographers who take perfectly-lit images of dishes for cookbooks.